Post World War II, the cosmetics industry experienced a boom as an exponential amount of beauty products was manufactured and on high demand. This seemingly limitless gamut of colors and styles altered the promotional strategies utilized by cosmetics firms while high powered advertising still proved fundamental to most big shot businesses, such as Revlon. In addition, manufacturers continued to practice market segmentation, the distribution of products through class, mass, and African American markets, but more distinct and nuanced groups, such as regional and age, began to form as the market appealed to a more diverse amount of people. By the 1950s, indelibility of lipstick and foundations became more popular, accentuating the artifice of makeup's performance, known as clean makeup. A psychological explanation for the use of cosmetics postwar was that the traumatic experiences of the men coming back had a negative impact on the women emotionally and took their jobs away; the only way to delve back into society was through feminine beauty as sexual allure and desire became more celebrated.

A 1952 Revlon ad for Fire and Ice lipstick ascertained that the "genuinely sexy woman is the 'good' woman" (pg 249) and marked the change of the tie-in of cosmetics and a self sufficient woman without the heterosexual appeal for a man. Cover Girl became a brand that appealed more to younger girls and was seen as for wholesome, nice girls; however, both these labels became standards of perfection many couldn't reach. Generational differences experienced conflict with their makeup styles as cosmetics increasingly became more sexualized and seen as a step towards womanhood as by the mid-sixties, a quarter of all cosmetics sales were bought by teenager girls. In addition, the well groomed, clean shaven look appealed to men as cosmetics targeted them by claiming rank and wealth were within reach if they could look the part, producing a new array of men's toiletries (cologne, aftershave, deodorants...). However, as an attempt to prevent effeminacy, commercials began to advocate sexual aggression towards women as an attempt to subdue to them in their place.

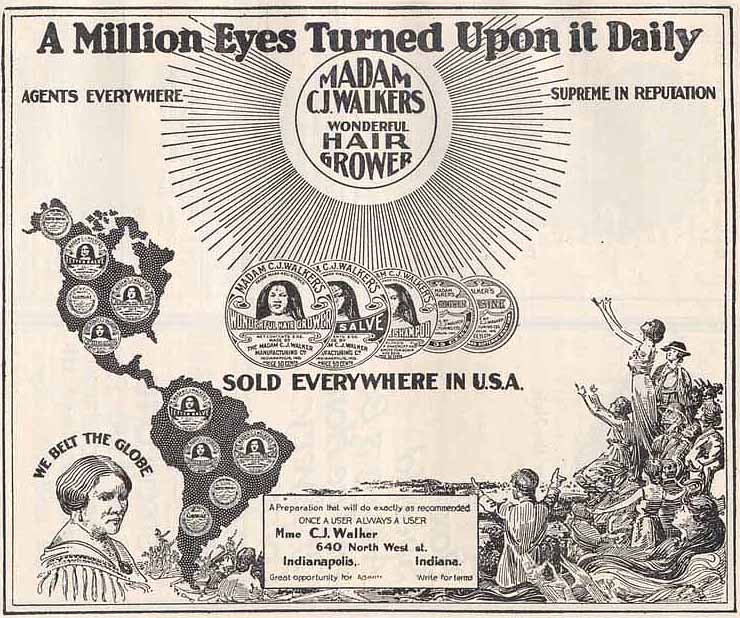

From the 1950s-1960s, criticism for cosmetics were muted but most of it came from working class women who struggled to maintain moral beauty through their long hours, insufficient wages, and illnesses that deprived them of their physical, youthful appearance. Most of the criticism came from African Americans who were increasingly protesting discrimination and segregation more assertively as more institutions and companies became integrated. In addition, the rise of Pan-Africanism decreased the sales of hair straighteners and bleaches as more African American women embraced their culture and traditional "unprocessed" hair. The natural look was becoming more prominent in the black community as more women began to condemn white aesthetics and European features in black magazines, like Ebony, retaining its political associations with black pride, authenticity, and freedom.

The 1960s counterculture of the natural body condemned the commercialization of the cosmetics industry as a cornerstone for women's oppression. The no makeup look was started by feminists caused manufacturers to change their advertising due to the attack on beauty products to be more asexual and hygienic rather than glamorous. Some, Mary Kay Ashley, infused feminist economic goals with traditionalist ideals of womanhood. Under increased pressure from colored women, many firms began to reevaluate and respond to racist advertising and products only meant for white women. Even as criticism surrounded the mass market of cosmetics, secret users were uncovered, especially men, as more businesses appealed to them publicly with skin treatments and moisturizers while promoting masculinity with cosmetics. The gay look also became popular among magazines with short hair, muscular body, and attentiveness to skin care as more men delved into the beauty culture, partaking in activities that were once shunned as unmanly. In addition, the ideal of perfection for women was redefined as criticism for models that looked too perfect rose in the middle class. The multicultural look extended to women of all walks, different ethnicities and sexualties, and lookism became known as discrimination which was barred from parts of society as women protested its unfairness.

Questions:

How did the natural counterculture have an effect on the men?

Why did cosmetics experience such an exponential growth post World War II?